Why Don't You Build a RL Computer?

Deep evolutionary and reinforcement learning algorithms are two of the most promising paths to understanding and developing general intelligence, but they have significantly different computational requirements than typical deep learning applications that tend to be focused on computer vision and supervised learning. Building your own workstation for RL/EA may be a daunting prospect, but compared to equivalent cloud compute the price of a self-built system can break even in just a few months of use. Read on to learn about the differences in building for RL vs. a typical deep learning box, and how how you can save thousands of dollars learning and developing with it. This is the first in a series of posts on how it's possible to do interesting and meaningful work on a self-built multicore PC while saving on costs substantially.

A Universe in a Box

"If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, first you must invent the universe." -Carl Sagan

Carl Sagan reminded us that all human experience depends on our universe and its exact set of physics, which are particularly well-suited to giving rise to a warm, meaty species of ape that can build interesting things with their brains and bodies. Imagine any one of a number of physical constants or laws were different and life becomes unfathomable. We can consider a similar thought experiment in the context of developing novel forms of intelligence. Building rich simulated environments in which machine agents can both learn and evolve in is one of the most promising routes for generating artificial general intelligence. If humans succeed in this venture before wiping themselves out, it will be a Big Deal, not least of all because it will help answer some of the Big Questions:

Human: Are there other intelligent beings in the universe beyond Earthlings?

AI: You're looking at one, Bub.

I’ve been building deep learning models since a few minutes after it was cool and a few years back I built a PC specifically for deep learning. The system was built around a pair of GTX 1060 6GB GPUs from Nvidia, and it massively accelerated my ability to iterate and experiment with image classification, segmentation, and pixel-to-pixel transformations, as well as machine learning for the optical inverse problems I work with professionally. A purpose-built system made a big difference in facilitating my learning curve, and this effect was amplified as I learned how to more effectively make use of both GPUs (and PyTorch and TensorFlow made it increasingly easy to train a model on multiple GPUs). I saved a lot of money by building my own system as compared to working through the same tutorials and experiments in GPU-enabled cloud instances, and the PC performs well at its intended objective of training deep convolutional models, mainly for vision. But performance specificity comes with a tradeoff, and in the past 6 months or so I’ve found that my deep learning box was falling short at certain tasks, particularly evolutionary algorithms and reinforcement learning.

Aside from notebooks like Google’s Colaboratory or Kaggle notebooks, I didn’t seriously give cloud computing a try until about the same time I started seriously studying reinforcement learning. A generous heap of Google Cloud Platform credits fell into my lap for competing in a NeurIPs 2019 reinforcement learning competition (Learning to Move Around). The goal of the competition was to learn a control policy for a biomechanical model of a human skeleton that could move toward a goal location. I found that while my system was probably overpowered with respect to running the control and value policy networks, it was spending most of the time computing physics for the reinforcement learning environment. This is typical for reinforcement learning, and consequently CPU performance is essential for fast learning in RL. Training on a measly 4 threads available on my budget CPU, my agent learned a rather pathetic local optima of face-planting enthusiastically in the general direction of the goal location* , which was nonetheless good enough for 10th place in the competition.

Using the credits from the competition, I began to familiarize myself with Google Compute Engine. With GCE, it’s easy to spin up an instance with 32, 64, 96, or even more vCPUs. This makes a big difference if you have the right workload. Meanwhile, I was spending more time studying open source implementations of of RL and evolutionary algorithms and I came to appreciate the importance of multi-threaded execution for these types of algorithms, many of which are embarrassingly parallel. Simulation is a cornerstone of reinforcement learning and evolution-based methods, and efficiently simulating rich environments in silico comes with its own set of hardware considerations and trade-offs. Since simulation is a big part of reinforcement learning, building a workstation specifically for RL has more in common with a build for simulating physics or rendering workflows than a ‘typical’ deep learning box. Of course this also means the resulting PC will be great for turning the knobs all the way up on Kerbal Space Program.

Why RL? Why EA?

You’re already familiar with the 2012 “ImageNet Moment” when a GPU-trained convolutional neural network from Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutstkever, and Geoffrey Hinton blew away the competition at the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. It was a big part of ushering in the (renascent) era of deep learning in general, but in particular it led to the widescale adoption of models and optimizers that could do pretty well on just about any image-based task. Transfer learning meant that a pre-trained network, even when trained on a vastly different task, could perform pretty well on a new task by replacing or re-initializing the parts of the network that put together higher-level abstractions and fine-tuning with a minimal amount of new training. Everything from image classification to semantic segmentation, and even caption generation can be amenable to this sort of transfer learning. In 2018 we saw the advent of very large, attention-based, transformer models for natural language processing, the impact of which has been strongly reminiscent of the original ImageNet Moment. Just like transfer learning with image-based models, big transformers pre-trained on a large non-specifc text corpus can be readily applied to new problem domains.

Even though reinforcement learning has seen major breakthroughs in the past decade, we are still arguably working toward a development at the scale and impact of AlexNet or the big transformer models. The AlphaGo lineage has decidedly disrupted the world of game-playing and machine learning in board games, and the latest iteration, MuZero, can play Go, chess, shogi, and Atari at a state-of-the-art level. But the model and policies learned by MuZero for chess can’t be used to improve its Go game or inspire strategies in Atari, let alone learning a new game or concepts about humans and game-playing in general. It’s only in the last few years that “training on the test set” has gone from an acceptable practice and sheepish inside joke to being something to be ashamed of, thanks to work on procedurally generated environments and richer simulations. We’re starting to see legitimately interesting progress in exploration, generalization, and simulation-to-real learning transfer. There’s also an ongoing resurgence in evolutionary algorithms that looks promising, especially when learning and evolution are combined. On top of all that, there’s an incredible contest playing out between more general, (and compute efficient) open-ended learning algorithms and more structured (and sample efficient) approaches like inverse reinforcement learning and model-based methods. On the way to understanding general intelligence, we can expect a slew of real-world applications in robotics control, electric grid management, and many other fields. I also predict fruitful cross-pollination between RL/EA research and computational physics as hardware, software, and algorithmic development accompanies increased interest. I hope you’ll tune in to future posts for discussions on the topics above, but in general let us agree that it’s a great time to work on these areas.

Build, Buy, or Rent?

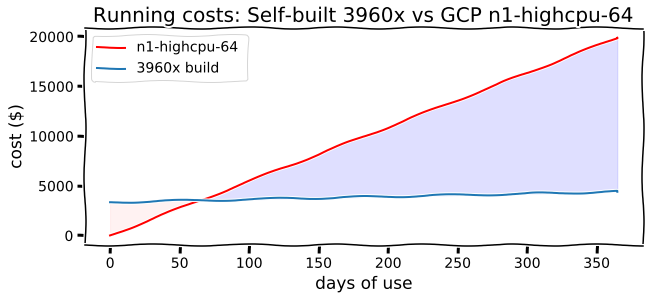

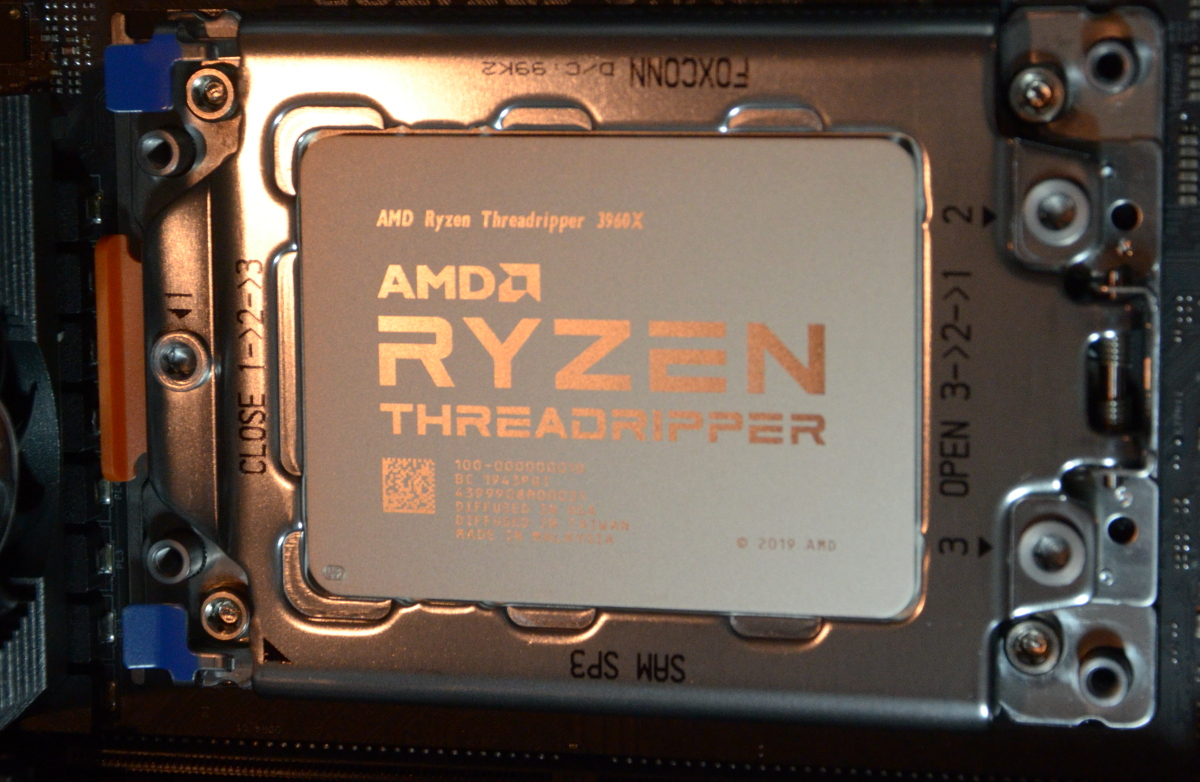

If you want to run experiments with multicore workloads, the cost advantage of a physical workstation over cloud-based virtual machines is undeniable. I built a deep reinforcement learning system based on the 3rd generation Ryzen 3960X Threadripper which handily outperforms n1-highcpu instances with 64 vCPUs on Google Compute Engine in my benchmarks (coming soon to a follow-up post near you!). Based on this build, the cost comparison is shown below.

The break-even point is about two months against on-demand Google Compute Engine instances (n1-high-cpu with 64 vCPUs vs the more expensive price list below). If you look at the figure, there’s quite a big gap in the cost of running the GCE instances versus a purpose-driven self-built machine over the course of a year of use, and I’ll cut through the suspense to tell you the difference is more than $15,000. That might sound like an overestimate, but in my benchmarks the 3960X build is almost twice as fast as a n1-highcpu-64 instance, so it’s actually probably an underestimate. The figure is based on usage time, not total time elapsed, so if you spend a significant amount of time iterating and building during the day, and regularly run experiments over nights and weekends, I would be surprised if you don’t break even before 4 months and save thousands of dollars in the first year, wall time.

Maybe the up-front cost of building at home is daunting, you are too nervous to risk bricking a high-end CPU that might cost more than a thousand dollars, or you just find the flexibility of cloud computing too appealing. Those are all valid reasons to pursue the cloud route instead, and if you do I suggest you spend some time optimizing for value efficiency. It’s easy to lose track of the fact that you pay for storage, even if your instances are shut down, so keep an eye on those enormous datasets. Worried you might forget to shut down a big compute instance? You should probably automate that. You can also decrease cloud costs substantially by purchasing committed instances in advance (about 30% cheaper) or by renting pre-emptible instances (almost 5x cheaper) although those could be, well, empted at any time.

If your interest is piqued, and I hope that it is, I’ve put together a couple of parts lists taking advantage of the latest generation of Ryzen CPUs from AMD. There’s a big budget option at about $3000 (it’s the build I went with) and a medium budget option at about $1000 less. If you have more cash burning a hole in your pocket you can also spend $500 to $1500 dollars more on the big budget option by upgrading to a 32-core Threadripper 3970X or a massive 64-core Threadripper 3990X. But keep in mind that Amdahl’s law limits parallelization speedups below scaling linearly with number of processes, so the 3990X won’t be twice as fast as the 3970X and the 3960X is the best performance-per-dollar of the new sTRX4 Threadripper chips.

Picking Parts

Souped-up, yet sane

| Component Type | Part | Price |

|---|---|---|

| CPU: | AMD Ryzen Threadripper 3960X 3.8 GHz 24-core TRX4 processor | $1499.99 |

| CPU Cooler | be quiet! Dark Rock Pro TR4 CPU air cooler | $89.90 |

| Motherboard: | ASRock TRX40 Creator TRX4 ATX motherboard | $459.99 |

| Memory: | Ballistix 64GB Sport LT Series DDR4 3200 MHz | $313.99 |

| Storage: | Samsung 1TB 970 EVO NVMe M.2 internal SSD | $169.99 |

| Video Card: | Gigabyte GeForce GTX 1060 6GB 6 GB WINDFORCE OC 6G Video Card | ~$210.00 |

| PSU: | SeaSonic FOCUS Plus Platinum 850 Watt 80+ Platinum Fully Modular ATX Power Supply | $154.99 |

| Case: | be quiet! Silent Base 601 Mid-Tower ATX Case | $129.00 |

| Monitor: | Dell S2419HN 23.8” 1920x1080 60 Hz Monitor | $159.79 |

| Keyboard | Das Keyboard Model S Professional Mechanical Keyboard (Gamma Zulu switches)** | $119.00 |

| Mouse: | Logitech Trackman Marble | $29.99 |

| Total: | $3336.63 | |

| Headless: | $3027.85 |

“Baby Threadripper”*** 3950x

| Component Type | Part | Price |

|---|---|---|

| CPU: | AMD Ryzen 9 3950X 3.5 GHz 16-Core Processor | $738.89 |

| CPU Cooler | be quiet! Dark Rock Pro TR4 CPU air cooler | $86.46 |

| Motherboard: | ASRock TRX40 Creator TRX4 ATX motherboard | $259.00 |

| Memory: | Ballistix 64GB Sport LT Series DDR4 3200 MHz | $313.99 |

| Storage: | Samsung 1TB 970 EVO NVMe M.2 internal SSD | $169.99 |

| Video Card: | Gigabyte GeForce GTX 1060 6GB 6 GB WINDFORCE OC 6G Video Card | ~$210.00 |

| PSU: | SeaSonic FOCUS Plus Platinum 850 Watt 80+ Platinum Fully Modular ATX Power Supply | $154.99 |

| Case: | be quiet! Silent Base 601 Mid-Tower ATX Case | $129.00 |

| Monitor: | Dell S2419HN 23.8” 1920x1080 60 Hz Monitor | $159.79 |

| Keyboard | Das Keyboard Model S Professional Mechanical Keyboard (Gamma Zulu switches)** | $119.00 |

| Mouse: | Logitech Trackman Marble | $29.99 |

| Total: | $2371.10 | |

| Headless: | $2062.32 |

After outgrowing free cloud notebooks, a good starting point for a deep learning build is Tim Dettmer’s full hardware guide. I suggest you give it a read. Afterward I suggest you forget about almost everything he says about CPUs being unimportant because a good multicore processor is the star of the show for a build focused on reinforcement learning, evolutionary algorithm, and physics. My build revolves around and is inspired by the impressive performance of the new generation of AMD Threadrippers. AMD has generated a significant lead in this niche of high end desktop CPUs accessible to mortals, and while I could have gone with the more expensive 32 or 64 core version the performance gains don’t quite justify the added expense (but it’s a tempting future upgrade). Some of the benchmarks I referred to are here, here, and here. On the GPU front, I was pleased to see that the GTX 1060 6GB GPUs I bought a few years ago have held up well, and the 1060 is still in third place in the Tim Dettmer’s updated performance-per-dollar list. I decided to use one of the GTX 1060 GPUs from a previous deep learning build. This is plenty for my current needs, which aren’t currently focused on computer vision, and I’ll probably wait for a significant development or price drop in the GPU space before upgrading.

My first impressions are of a very capable build. I’ve ran a few training flows on both the Threadripper workstation and Google’s n1-highcpu-64 cloud instances and the RL PC tends to be much faster. The machine is fun to work with, and can mean the difference between abandoning an idea early and finding an interesting unexpected result. Running on a measly 4 threads, an experiment may only yield ambiguous results given a reasonable amount of time, and iterating to those first few signs of learning using cloud compute can be expensive. A purpose-built setup like this one lets you answer questions and iterate much faster, making new experimentation and lines of inquiry tractable. If this article has been informative, stick around. In future posts I’ll detail the build process, software setup, and benchmarks.

Footnotes

* In the end I settled on training with the Spinning Up repository from Joshua Achiam at OpenAI. This is a great resource (now with PyTorch implementations) and I highly recommended playing around with it. back to text

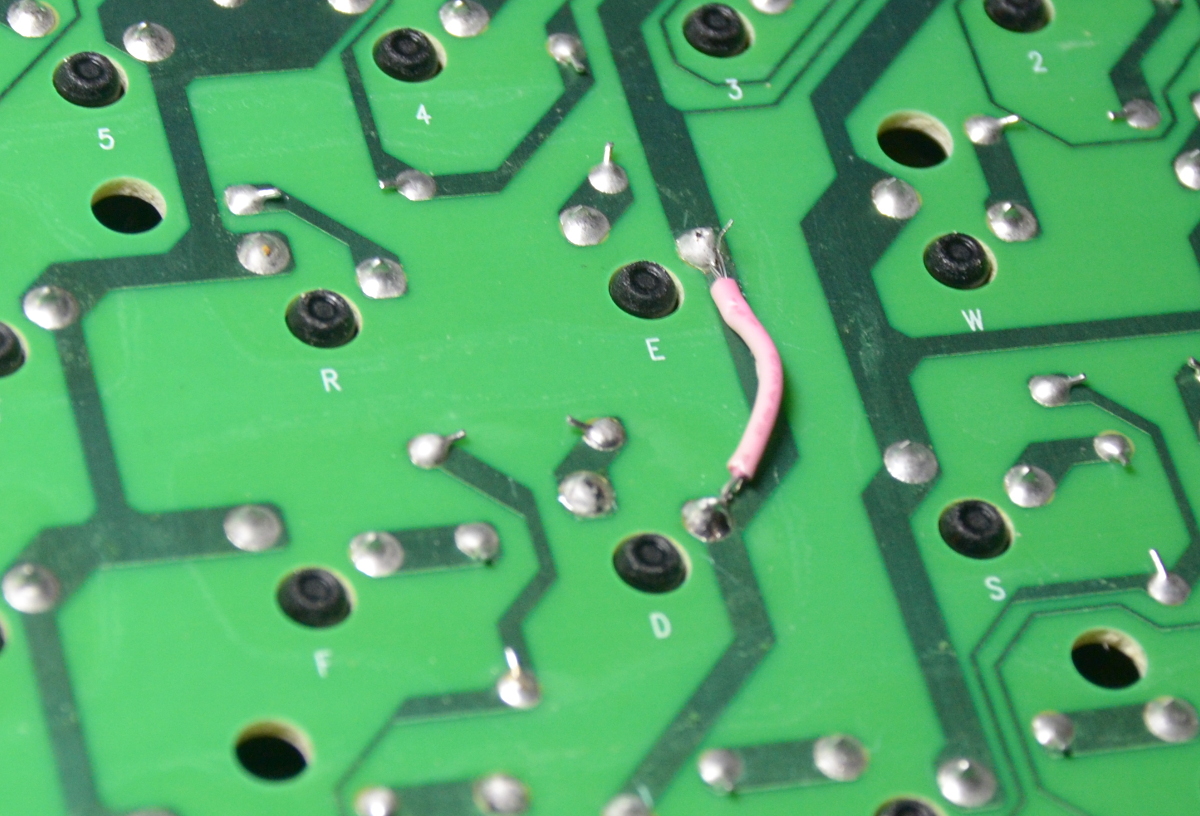

After a bit of reading, I was excited to settle on a ~$120 mechanical keyboard from Das Keyboard with Gamma Zulu (similar to Cherry Mx Brown) switches. Be aware, I had major problems with this keyboad. Some short minutes after receiving the keyboard I pulled it out of the box and plugged it into my laptop (the RL box wasn’t built yet), and began typing away. The keyboard has a firm tactile and auditory feedback that leaves no doubt in one’s mind that you are, in fact, typing. But this one was defective, as it soon become obvious that the c and d keys were not responding. I fired up xev and confirmed that, yep, no signal was making it from the keyboard through the USB when I pressed those keys normally. I did find that if I pressed the d key really, really hard it would respond, but had no such luck on the c key.

Other than not working, I had a good impression of the keyboard. It’s much louder than the more common keyboards built around a domed plastic membrane instead of mechanical switches, and for speedy typists that will probably be a problem in shared offices or for long periods (maybe a great way to clear out your private corner of a cube-less cubicle farm?). The keyboard is fast and it feels pretty nice. But I have to say that if you charge $119.00 for a keyboard, you should be able to afford good quality control.

I decided to void the warranty and popped the keyboard open, peeling away the “do not remove- OK” sticker to get to the last screw. I lost a few small plastic tabs along the way, and it is disappointing that supposedly durable goods like this are not designed specifically with repairability in mind. Using a multimeter, I found the switches were closing the circuit as expected when pressed (I initially thought would be repairing or replacing the switches themselves). More probing with the multimeter revealed that a rail shared by c, d, e, and 3 keys wasn’t connected all the way through. In particular there wasn’t a reliable connection between the pins for the d and e keys (although as mentioned before excessive force on the d key sometimes closed the circuit). I soldered a jumper wire from the pins with the misbehaving connecting trace and things started worked properly.

Now that the keys work this is a great keyboard.

*** The 3950x is not a part of the Threadripper lineup, but it is fast.