The RL Contest Between Cloud and Home Builds: Threadripper vs. the Cloud, Setup and Benchmarks

This is the second in a series of posts on how it's possible to do interesting and meaningful work in reinforcement or evolutionary learning on a self-built multicore PC while saving on costs substantially. The previous post describes motivation and parts selection. We've already discussed how a self-built PC is thousands of dollars cheaper for these tasks than on-demand cloud instances, but how does performance compare? In this post we'll run a few reinforcement learning and evolutionary algorithms to compare a self-built RL PC based on the 24 core 3960x Threadripper CPU and a `n1-highcpu-64` virtual machine instance with 64 vCPUs from Google Compute Engine.

Setup and Experiments

Setup: Self-Built 3960x Threadripper System

Benchmarking this PC was the first thing I did after getting everything put together and working. I started with a fresh install of Ubuntu 18, and all the Python code I used has permissive licensing, so the commands below should suffice to replicate these experiments. If you run these benchmarks on your own machine I’ll be interested to see your results, espeecially if you run them with a build based on one of the 3950x, 3970x, 3990x CPUs from AMD, a comparable Intel chip, or even another cloud compute setup.

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get --assume-yes upgrade

Now this isn’t a computer vision-centric deep learning build, so I am using an older 1060 GTX 6GB card from Nvidia (which still stacks up pretty well as a consumer card for deep learning, value-wise). While reinforcement learning and evolutionary algorithms do tend to rely heavily on a fast multi-threaded CPU compared to supervised learning where GPUs are most important, the best results come from leveraging the strengths of both. We saw this a few years ago in some work from Uber AI Labs on Atari, complimenting work on fast learning with evolutionary strategies from OpenAI, and a great deal many other cool projects besides. It’s common to use fairly small neural networks in RL, and when that’s the case it definitely will feel like a waste moving your neural network over to the GPU to perform a few dozen matrix multiplies with 32 by 32 hidden layers, and that’s probably true. However, those small network architectures probably have a lot to do with the history of “training on the test set” in RL and the field is moving away from that somewhat embarassing practice with procedurally generated environments, better domain randomization, and other tricks.

My notes for setting up GPU drivers and the CUDA primitives used for neural networks:

sudo apt-get --assume-yes install tmux build-essential gcc g++ make binutils software-properties-common vim

wget -O cuda.deb http://developer.download.nvidia.com/compute/cuda/repos/ubuntu1804/x86_64/cuda-repo-ubuntu1804_10.1.105-1_amd64.deb

sudo apt-key adv --fetch-keys http://developer.download.nvidia.com/compute/cuda/repos/ubuntu1804/x86_64/7fa2af80.pub

sudo dpkg -i cuda.deb

sudo apt-get update

# find the driver for your card at https://www.nvidia.com/download/index.aspx

#Version: 440.64

#Release Date: 2020.2.28

#Operating System: Linux 64-bit

#Language: English (US)

#File Size: 134.76 MBd

sudo telinit 3

# disable nouveau - I ran the following as a shell script before installing the NVIDIA driver

sudo bash -c "echo blacklist nouveau > /etc/modprobe.d/blacklist-nvidia-nouveau.conf"

sudo bash -c "echo options nouveau modeset=0 >> /etc/modprobe.d/blacklist-nvidia-nouveau.conf"

# check

cat /etc/modprobe.d/blacklist-nvidia-nouveau.conf

sudo update-initramfs -u

sudo reboot

sudo telinit 3

cd path/to/nvidia_driver_folder

sudo sh NVIDIA-Linux-x86_64-440.64.run

# check nvidia driver is installed

nvidia-smi

# should look something like

#+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------+

#| NVIDIA-SMI 440.64 Driver Version: 440.64 CUDA Version: 10.2 |

#|-------------------------------+----------------------+----------------------+

#| GPU Name Persistence-M| Bus-Id Disp.A | Volatile Uncorr. ECC |

#| Fan Temp Perf Pwr:Usage/Cap| Memory-Usage | GPU-Util Compute M. |

#|===============================+======================+======================|

#| 0 GeForce GTX 106... Off | 00000000:01:00.0 On | N/A |

#| 0% 51C P0 27W / 120W | 156MiB / 6070MiB | 0% Default |

#+-------------------------------+----------------------+----------------------+

sudo apt-get install --assume-yes cuda-toolkit-10-2 cuda-command-line-tools-10-2

# to install cuDNN you'll need to set up a developer account with NVIDIA

# check nvcc version

nvcc --version

# if nvcc is not found, may need to add to path e.g.

# find it

echo "export PATH=/usr/local/cuda-10.2/bin${PATH:+:${PATH}}" >> ~/.profile

source ~/.profile

# now this should work

nvcc --version

Setup: Google Compute Engine n1-highcpu-64 Instance

I compared my self-build 3960x PC to the n1-highcpu-64 VM instance on Google Compute Engine. Keep in mind that when cloud VMs are described as having a certain number of vCPUs (64 in this case), this is referring to the number of threads rather than the typical 2-thread cores in CPU specs. Even so, the cloud VM has 33% more threads available than the 3960x and we might naively expect that highly parallel algorithms will run faster on the GCP VM (this would be wrong).

I ran out of space to install all the required frameworks and repositories using the default setting storage option of 10 GB, so I upped this to 64 GB in order to run the benchmarks. The first benchmark uses Spinning up in Deep RL from Joshua Achiam at OpenAI and others, which meant the first step to getting the VM ready was upgrading python to 3.7 (the Debian image defaults to 3.5 and Spinning Up requires 3.6+). I followed tips from StackOverflow to upgrade python using the following commands:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install -y build-essential checkinstall libreadline-gplv2-dev libncursesw5-dev libssl-dev libsqlite3-dev tk-dev libgdbm-dev libc6-dev libbz2-dev zlib1g-dev openssl libffi-dev python3-dev python3-setuptools wget

mkdir python37

cd python37o

wget https://www.python.org/ftp/python/3.7.0/Python-3.7.0.tar.xz

tar xvf Python-3.7.0.tar.xz

cd ./Python-3.7.0

./configure

sudo make altinstall

alias python=python3.7

cd ../../

Preparation and Launching Experiments

Once the cloud instance/3960x build is ready, setting up the needed virtual environment and launching experiments should be identical for both platforms.

Benchmark 1: PPO with Spinning Up

Spinning Up in Deep RL is a great resource that combines educational resources and implementations of many deep RL algorithms. The PPO implementation from Spinning Up will be the first RL benchmark for this build, and getting the repository up and running with all dependencies is just a few lines:

mkdir benchmarks

cd benchmarks

sudo apt-get install -y virtualenv libopenmpi-dev python-dev git htop tmux

virtualenv ./spinup --python=python3.7

source ./spinup/bin/activate

git clone https://github.com/openai/spinningup.git

cd spinningup

pip install tensorflow==1.14

pip install -e .

The actual experiment is 40000 steps per each of 1000 epochs for three random seeds and using 40 threads. I ran into some trouble with cryptic mpi errors when trying to use more than 40 threads, so both the GCP and the 3960x build will use 40 or less on this benchmark.

python -m spinup.run ppo --hid "[32,32]" --env BipedalWalker-v3 --exp_name exp_name --gamma 0.999 --epochs 1000 --steps_per_epoch 40000 --seed 13 42 1337 --cpu 40

Benchmark 2: Evolving Pruned Networks

I used the same virtualenv for the second benchmark, a genetic algorithm based on applying selective pressure to pruned neural networks. This is my own work and has an early blog post describing the idea here. The parallelized version of this algorithm uses MPI (for python) and is able to fill up all the threads available on the GCP VM. Note that the -n flag designating the number of CPU threads refers to the worker processes only, making the total thread n+1 including the coordinating process.

git clone https://github.com/rivesunder/synaptolytic-learning.git

cd synaptolytic-learning

git checkout 89f4dbb1a538e3827a9e45a0560ff8522889b0af

pip install -r requirements.txt

And to run the experiment:

python3 src/mpi_simple.py -e BipedalWalker-v2 -r 8 -a HebbianDagAgent -n 63 -p 138 -g 200 -d 8 8 -s 13 41337

Results

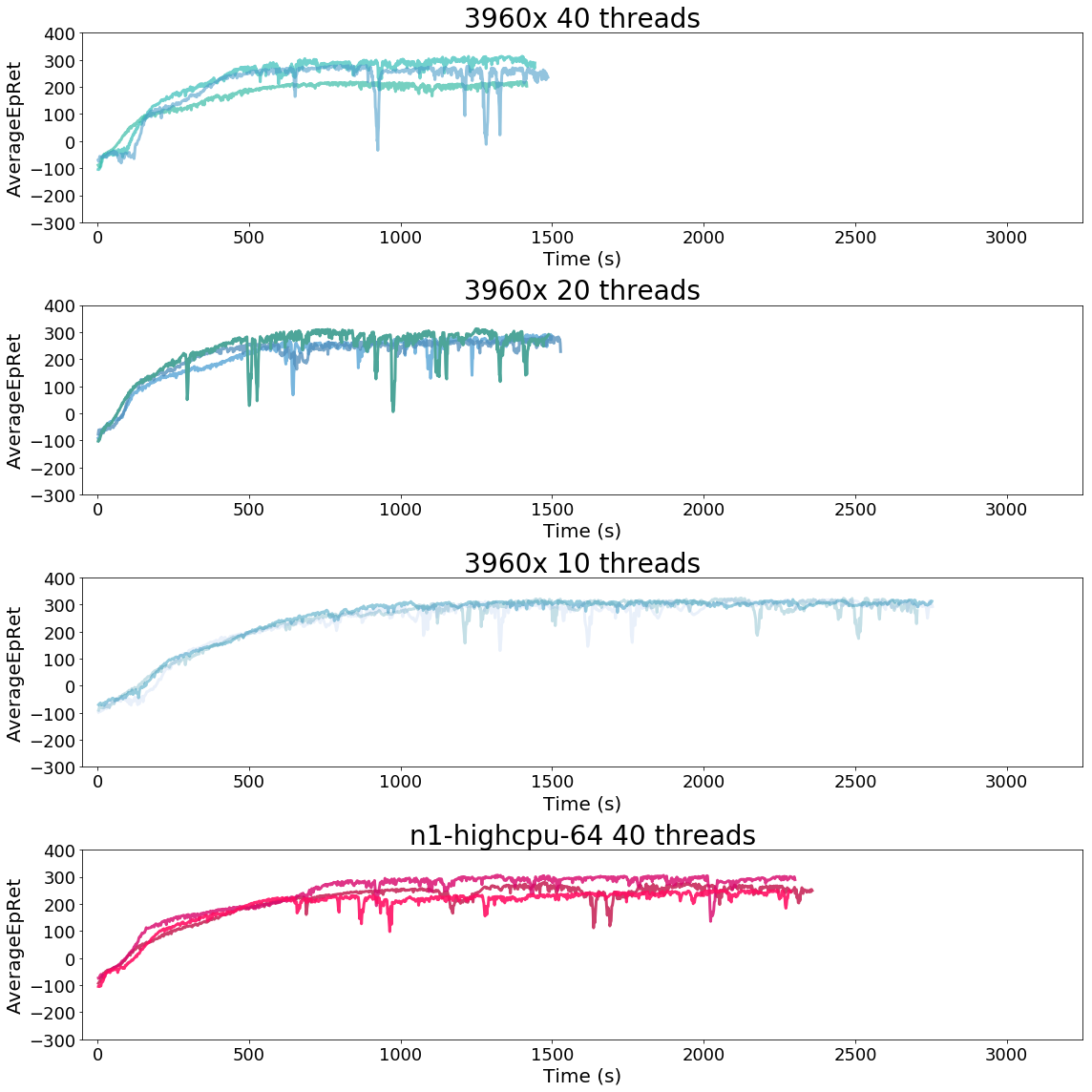

Benchmark 1: PPO (Implementation from Spinning Up)

PPO from Spinning Up (BipedalWalker-v2) |

1000 Epochs |

|---|---|

| 3960x PC (40 threads) | 1448.36 +/- 28.71 s |

| 3960x PC (20 threads) | 1504.64 +/- 16.86 s |

| 3960x PC (10 threads) | 2737.47 +/- 23.30 s |

| n1-highcpu-64 | 2315.26 +/- 30.62 s |

As we can see in the figure above, the 3960x build is substantially faster than n1-highcpu-64, even when running on half as many cores. In fact, dropping from 40 down to 20 cores doesn’t seem to slow PPO down significantly at all. That suggests to a serial computation bottleneck, probably related to PPO’s training overhead, which involves computing the KL divergence to stabilize policy changes. Presumedly that means you could run 2 separate PPO experiments simultaneously in much less than twice the time required for a single experiment.

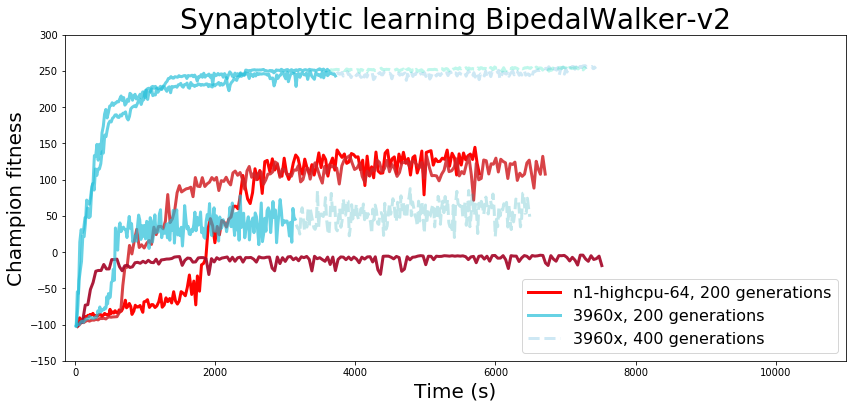

Benchmark 2: Synaptolysis

Enthusiastic agent

Evolutionary Algorithms are sometimes referred to as “embarrassingly parallel” because they are so amenable to parallel implementations. Unlike the policy gradient-based learning algorithm in the first benchmark, evolutionary algorithms have less overhead because they don’t have to compute additional overhead like the KL divergence of the policies. Generally speaking, they don’t even have to compute gradients! The only place where a single-thread bottleneck is really necessary in a genetic algorithm is to sort and update the agent policies by best fitness. There is an interesting and somewhat counter-intuitive trade-off that occurs fairly often in reinforcement learning: sample efficient methods like PPO (and imitation, model-based, inverse RL, etc. to a greater extent) don’t need to experience as much simulator time to come up with a good solution, but in terms of wall time (and hence compute and energy expenditure) simple algorithms like EAs often do better. The competition and where this trade-off breaks down seems like a productive area to study to me.

In any case, in this benchmark the performance differences between the self-built PC and the GCP cloud instance were even greater, despite the fact that this algorithm implementation is able to take advantage of all 64 threads on a n1-highcpu-64 VM.

Evolving Pruned Networks (BipedalWalker-v2) |

200 Generations | 400 Generations |

|---|---|---|

| 3960x PC | 3491.69 +/- 251.76 s | 7070.26 +/- 414.93 |

| n1-highcpu-64 | 6666.38 +/- 714.00 s | - |

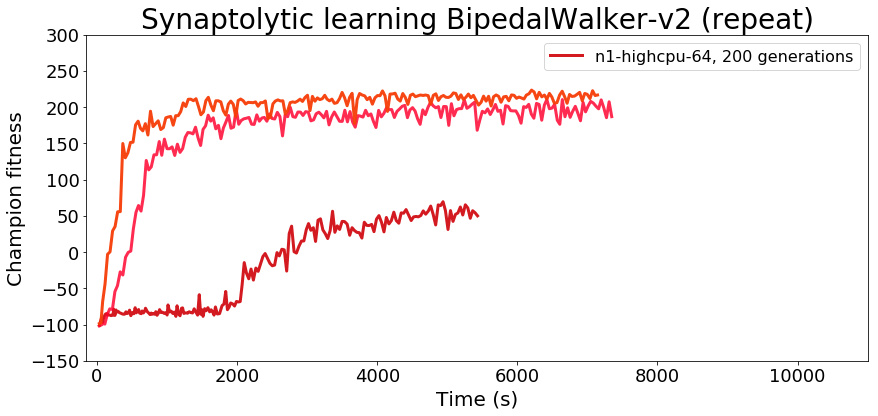

You’ll notice that the fitness metrics are quite different between the 3960x build and the cloud instance. The fitness performance seemed to disfavor the cloud instance enough that I spent some time double-checking to make sure the commits were identical and I hadn’t overlooked a last-minute change in the code somewhere. As it turns out, repeatable, deterministic psuedo-random number generation in multithreaded applications can be a bit tricky, something I didn’t consider when setting up the training. Although the coordinator process initializes the population and handles all population updates (pulling from one random number generator initialized with the experiment’s seed), each worker process will instantiate its own version of the environment and the different environments will all pull random numbers for things like initialization state, and they may call their random number generators in any order, eventually yielding a sort of butterfly effect as small differences early on lead to big differences later. It’s easy to overlook a lack of determinism in multithreaded pseudo-random number generation, and this probably comes into play more often than is immediately obvious in RL/EA. Looking more closely at the first benchmark it’s obvious that Spinning Up’s PPO is also non-deterministic despite using identical seeds as well.

We can see in the second run of the experiment on GCP that training can differ significantly between different runs of the same experiment definition.

Conclusion

Saving money by building a high-end desktop with a modern multicore processor doesn’t mean sacrificing performance on reinforcement learning and evolutionary algorithms. In fact, for the benchmarks investigated here, comparable cloud compute can take more than 190% as long for some experiments. The benchmarking above above was entirely a CPUs to vCPUs comparison: my pruned evolution algorithm is written entirely in numpy and I didn’t find anywhere in the new PyTorch backend in spinning up that moves data to the GPU. I would expect that a CPU/GPU-dependent training algo would widen the gap in performance-per-dollar even further, if anything, based on the benchmarks and cloud comparisons I’ve seen before. In future projects I will investigate how best to leverage CPU and GPU (or other accelerators) together for more realistic RL problems.

OpenAI’s cloud bill as a non-profit was more than $7.9 million in 2017 according to their 990 tax form, and you can bet they’re not paying retail prices. From news like that it would be easy to conclude RL is only open to the deep-pocketed elite, but I hope this post will encourage a person or two somewhere, or maybe even a small team, to realize that you don’t necessarily need a huge cloud compute budget to learn and do good work in RL/EA. And, as I mentioned earlier, if anyone runs these benchmarks on their own build I’d be interested to read about the results. I’m especially curious as to how a “Baby Threadripper” 3950x CPU system stacks up. The 3950x is spec’ed a lot slimmer than the 3960x, but at half the price and given the performance advantage of the 3960x over n1-highcpu-64 I’d be surprised if it doesn’t offer good value against general-use cloud VMs.

Build Guides and Resources for Building Your Own Deep Learning PC

There have been a lot of good blog posts about building deep learning computers with consumer hardware, and I’ve found their build notes, install guides, and cloud cost breakdowns useful over the years. A few of them are linked below, with my thanks to the authors. Not that my thanks are linked below, that’s more of an abstract concept not amenable to hypertext, but I’m sure you get the idea. Also thanks to you for reading. As a reward for reading the whole thing, the part you’ve all been waiting for is coming up next: bloopers.

- Tim Dettmers

- Slav Ivanov

- Nick Condo

- pcpartpicker.com Use this site to figure out which components are compatible before ordering a box of parts!

Bloopers

Most mutations do not improve an organism’s fitness and these genetic algorithm training excerpts are no exception.